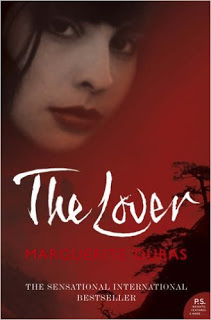

Chaucer draws on these legal issues in revising Livy’s story of alleged abduction of Virginia and the threat of rape. The intertextual, comparative approach adopted problematises critical assertions of a reductive opposition between the monolithic, racist discourse of colonialism, on the one hand, and the multi-faceted hybridity of post-colonial texts, on the other.Ĭhaucer’s Physician’s Tale addresses the issues of female victimization and battered women’s agency in medieval law and in particular the statute of 1382 authorizing a woman’s paternal guardians to appeal the crime of sexual assault and abduction regardless of the woman’s consent. Duras’s repeated textual returns to colonial Indochina and its people, over a period of more than fifty years and spanning both colonial and post-colonial eras, propaganda and fiction, offer particularly fertile ground for the exploration of the nature, uses and permutations of colonial discourse, and of representations of the East, as evidenced in the works of one author. My study thus examines how tropes, stereotypes and motifs of colonial discourse, originally employed in L’Empire français’s eulogistic and propagandist portrayal of ‘la plus belle des colonies françaises’, are borrowed and adapted in Duras’s later, polyvalent, literary representations of Indochina. This study analyses Duras’s first and long-overlooked propagandist work, L’Empire français, as intertextual precursor to her later, ‘Indochinese’ literary works, Un barrage contre le Pacifique (1950), L’Amant (1984) and L’Amant de la Chine du Nord (1991). Although Duras never physically returned to her ‘pulverised’ pays natal, her literary works attest to a repeated figurative return to the Indochina of her childhood, as originary source of creative inspiration and as the professed key to her writerly imaginary.

Born as the child of impoverished colons in the colonial outpost of French Indochina in 1914, Duras left the country of her birth and childhood at the age of eighteen, never to return. ‘Je suis quelqu’un qui ne sera jamais revenu dans son pays natal’, Duras stated in 1987, so simultaneously defining herself in relation to the place of her birth and as eternally displaced from it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)